Enlarged photos of Fred “The Fox” Snowden with his casual, yet endearing smile, were placed in various spots of The Loft Cinema on Friday night.

The marquee outside read “Fred Snowden Tribute” with other events happening at The Loft. Snowden, who made coaches shows on TV popular with The Fred Snowden Show on the old KZAZ-Channel 11, deserved the marquee to himself.

Players, family members and fans from The Fox’s time coaching Arizona from 1972-81 filled the seats. Some, such as Sahuaro High School football coach Al Alexander, mentioned it was learned for the first time Snowden’s glorious and meaningful past.

The feeling entering the The Loft on Friday night was welcoming much like Tucsonans experienced walking into McKale Center 50 years ago for the first time on Feb. 1, 1973, when the Wildcats played the first game there against Wyoming.

Folks back then wanted to see Snowden, hired 50 years ago as the first African-American coach to lead a major-college program, and the Kiddie Korps on a grander stage after their exciting transition-style brand of basketball created a buzz and sold out the 3,000-seat Bear Down Gym for two-thirds of the 1972-73 season.

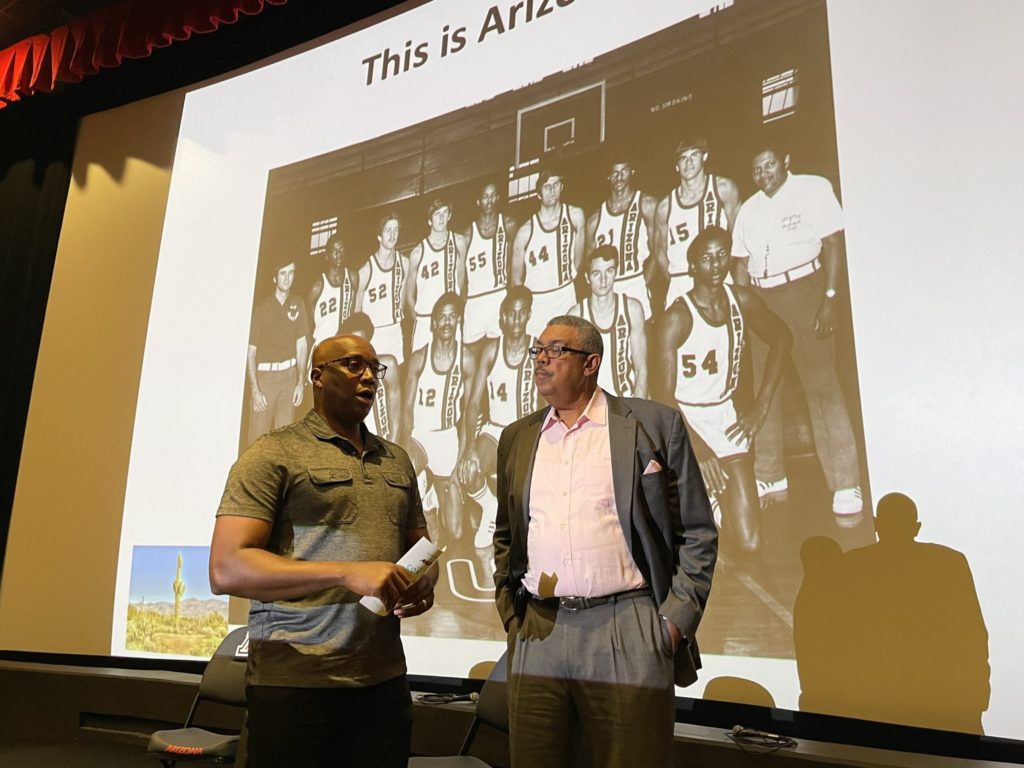

Stacey Snowden, the daughter of Fred and Maya, took center stage with Bob “Big Bird” Elliott, with the large screen behind them showing photos and videos of the history of The Fox from his days in Michigan to when he made Tucson become a basketball town before Lute Olson arrived.

“A Fireside Chat with Stacey Snowden” presented by the new African-American Museum of Southern Arizona was a captivating way to start Black History Month.

Some of the highlights:

— Some of Snowden’s former players including Elliott, Eric Money, Joe Nehls, John Belobraydic, Steve Kanner, Donald Mellon, Harvey Thompson, Bob Aleksa, Gary Harrison and Herm Harris were in attendance along with Snowden’s recruiting ace of an assistant, Jerry Holmes, who said Friday night that he “brought in about 90 percent of the players and Coach Snowden sealed the deal.”

— Don Strack Jr., son of former Arizona athletic director Don Strack, was in attendance. Strack Sr. hired Fred Snowden as the first African-American assistant in college basketball history at Michigan before bringing him to Tucson.

— Arizona coach Tommy Lloyd and his assistants Steve Robinson and Jason Gardner were there along with graduate transfer Cedric Henderson.

— Bob Elliott introduced his wife Beverley and their grandson Jody, who created the idea for the African-American Museum of Southern Arizona after noticing other cities had such an important place. The Elliotts credit Jody for providing the impetus for the first African-American Museum in Arizona.

— Stacey began the event clearing up an inaccuracy reported in Tucson after her father arrived here from Ann Arbor, Mich., following his birth in Brewton, Ala., and moving to Detroit when he was 6 with his mom and two brothers to attend school there.

“A reporter, at some point, said that he was a son of a sharecropper,” Stacey said of her dad. “We’ve spent the last 50 years trying to get that story cleared up because his grandfather was a sharecropper. So he spent his early years on that farm in (Alabama) doing a lot of hard work. And he says that is what helped prepare him to become a great athlete and also a coach later.

“My grandfather — my father’s father — was actually a war veteran. He was a math professor. He went to the University of Alabama. He got his master’s degree in math, and he was a teacher throughout his whole career. The reason I bring that story up is that those kinds of things are such a sense of pride with all families, but especially within black families, and black families in the South.

“So back at that time when the story had gotten in the newspaper and on the AP wire and then got to the South and so forth, and in Michigan, my family was like, ‘a Sharecropper’s son?” What are you guys doing down there in Tucson? What is this about? So I wanted to clear that up, finally.”

Fred Snowden was a scholar himself, earning a bachelor’s and master’s degree in English at Wayne State at Detroit.

— After Fred Snowden’s passing at age 57 in 1994 from a heart attack, Stacey came across her father’s personal written reflections titled “My Manuscript Partial.” Included in that was his apprehension at first at coming to Arizona as the first African-American head basketball coach at a major university because of the racism his family might encounter by making that move.

She became emotional remembering as a child the telephone conversations her father had with John Thompson, hired as Georgetown’s coach in 1972 after Strack lured Snowden. They talked with each other many times at night after the games their teams played.

“It was some tough stuff to hear,” she said. “They would talk a little bit about the game and the sport and what they were doing then, but they mostly talked about how they were going to get through the racism they were going through.

“It was tough.”

Snowden and his family were told they were not allowed to buy a house at 1841 N. Tucson Blvd. in the Catalina Vista neighborhood near Elm Street and Tucson Boulevard because “black people were not allowed to live there,” Bob Elliott said. Maya Snowden requested a couple of her Caucasian friends to act like they wanted to buy the house and the developers were enthusiastic about selling the home to them.

“The builder actually told my mom’s friend, ‘We don’t want blacks here,'” Stacey said. “My parents filed a lawsuit and they won, and they said, ‘You can keep your house, no thank you, but we are doing this so others don’t have to go through it.’ That was his feeling about taking this job here at Arizona — pave the way, hope you’re not the last.”

Stacey mentioned that in his manuscript, her father was very conscientious “as a black man, as a black coach going through the interview process” at Arizona of how he should dress and conduct himself with the concern of prejudices from others.

“All these things, he knew he was going to be judged by,” she said. “He came to Arizona, did the interviews, met with the Board of Regents, whole 9 yards. Everything goes great. They made the offer. He goes back home to Detroit and then it really started to hit him. This is a lot. Maybe there will be another opportunity closer to home if he was going to be the first (black coach) if that’s what’s meant to be.

“He really had reservations about coming out here, about coming this far from his family, from what he knew, from the community, from the diverse community that we were part of. He gets home and tells my mom, ‘I think I change my mind. I don’t want to do this.’ They stayed up all night talking about this. He had really changed his mind and decided he was not going to do it. My mom pushed him to do it. She said, ‘Fred, you deserve this. You’ve worked hard for this. This is your opportunity. Don’t worry about the rest of us. We’ll be okay.'”

After saying that, Stacey looked up at the ceiling and laughed because they weren’t always okay because of the racism they did encounter after coming to Tucson.

“He went ahead and took the job,” she continued. “Dave Strack called him the next day. He told him, ‘Dave, you almost didn’t have a coach.’ He said, ‘Fox, please don’t tell me that.’ He said, ‘No, no, I’m coming.'”

Fred Snowden was cautious in the interview process to the point that he was apprehensive drinking a cocktail offered to him at the former Plaza International at Campbell and Speedway (now called The Loft).

“They ask my father, ‘Coach, would you like to have a drink?'” Stacey said. “My father goes through a couple of paragraphs in his manuscript of this whole process of, ‘Should I have a drink? Is this just a friendly gesture? Is it something else? Do they want to see me as the kind of person that I have to have a drink?’ The pressure — he went through this whole thing because he was thinking of, ‘Are they viewing me as a black man?’ He ended up deciding to order a drink and it ended up being just that, a gesture of ‘do you want a drink?’ There was nothing behind it. But these were the type of things that he had to think about as a black coach.”

Stacey also spoke about the dangers the family encountered in Tucson.

“There was always a bomb threat, a kidnap-torture threat … I had to evacuate my home more times than I can count and we were just trying to build a program,” she said.

— One of the videos showed Snowden’s national recruiting effort in his first two seasons, including the gathering of the iconic “Kiddie Korps” in his first season right after freshmen were made eligible by the NCAA. The freshman starters in 1972-73 included Money and Coniel Norman of Detroit, Jim Rappis of Waukesha, Wis., Al Fleming of Michigan City, Ind., and John Irving of Wilmington, Del. Elliott arrived the following season from Ann Arbor along with Gary Harrison from Detroit and Len Gordy and Herman Harris from Chester, Pa.

“Coach had charisma and plenty of swag,” Money said in the video, which showed Fred Snowden with the Temptations, Dionne Warwick, Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Nelson Mandela, Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young and Bill Clinton.

Snowden immediately endeared himself to Arizona fans because he brought a fast-paced, high-scoring style of basketball that made McKale Center electric from the start. In his fourth season, he took Arizona to its first Elite Eight appearance, when it lost to UCLA at Pauley Pavilion after remaining close with the Bruins until about 8 minutes remained.

— The event Friday also showed Fred Snowden in his business life after coaching as an executive with Baskin-Robbins and also the executive director of the Food 4 Less Foundation in Los Angeles. Snowden was in Washington, D.C., in 1994 to attend a White House ceremony in which Clinton unveiled plans for “empowerment zones” to develop urban and rural areas in which Fred Snowden was an active participant. That’s when Fred Snowden passed away from a heart attack.

— His legacy continues at Arizona not only as the first African-American to coach a major college basketball team but the spark the university needed to become a national program going from the WAC to the Pac-10. Olson arrived in 1983 two years after Snowden coached his last game at Arizona. The fact that Snowden showed Tucson can support the Wildcats with sellout crowds was a factor in Olson taking the job. Olson actually coached against Snowden and Arizona while at Iowa in a holiday tournament at Hawaii on Dec. 29, 1975. Iowa held on to win 82-80 after taking a 35-7 lead 12 minutes into the game. “At the conclusion of the game, Freddie Snowden did his postgame show out in the middle of the court,” Olson told me in a 1996 interview for The Arizona Daily Star. “It was certainly an indication of good fans and a big-time program. There were a lot of Arizona fans there.”

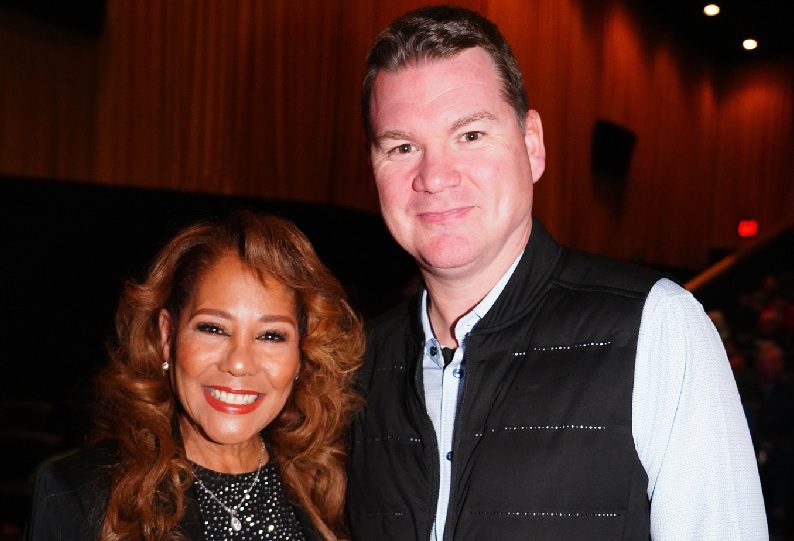

— A Community Impact Panel took part in the Fireside Chat that included Delano Price, longtime educator and basketball coach in the community; Dr. Michael Engs, who has engaged in research on the contributions of African-American communities to Arizona and works with projects at the Dunbar Pavilion African American Arts and Cultural Center; and Clint Peek, an entrepreneur who helped in the development of the African-American Museum of Southern Arizona.

Belobraydic, Kanner and Miller also shared stories as Fred Snowden’s former players.

One of the most gripping accounts of how Fred Snowden made an impact was told by Miller, who became an educator and administrator and also officiated youth sports after playing at Arizona from 1979-81 following his arrival from Philadelphia.

Miller recounted when Fred Snowden talked him and others into going with him to visit the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Tucson as a way to reach out to the community. Miller said at first he didn’t want to go, but he became enlightened to how he and the Wildcats can positively impact people after meeting patients there.

Fred Snowden’s words to him that day are forever in his mind.

“He said, ‘It’s not the points you score on the court,'” Miller said while sobbing. “‘It’s the points you score off the court.'”

— Arizona’s athletic director Dave Heeke was at The Loft Cinema on Friday night with Arizona Athletics being the title sponsor. Other sponsors were Cox Cable, Tucson Electric Power, Zuckerman Family Foundation, Bob and Beverley Elliott Family Charity, Ken’s Hardwood Barbecue, The Loft Cinema, Tucson Appliance Company, Arizona Confluence Center for Creative Inquiry, Arizona College of Humanities Africana Studies, the Arizona Foundation, Pima Community College, Richard and Doreen Davis, Arizona Health, Bon Voyage Travel and the Udall Law Firm.

INTERVIEWS

FIRESIDE CHAT

FOLLOW @JAVIERJMORALES ON TWITTER!

ALLSPORTSTUCSON.com publisher, writer and editor Javier Morales is a former Arizona Press Club award winner. He is a former Arizona Daily Star beat reporter for the Arizona basketball team, including when the Wildcats won the 1996-97 NCAA title. He has also written articles for CollegeAD.com, Bleacher Report, Lindy’s Sports, TucsonCitizen.com, The Arizona Republic, Sporting News and Baseball America, among many other publications. He has also authored the book “The Highest Form of Living”, which is available at Amazon. He became an educator five years ago and is presently a special education teacher at Gallego Fine Arts Intermediate in the Sunnyside Unified School District.