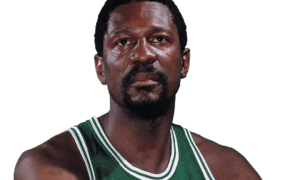

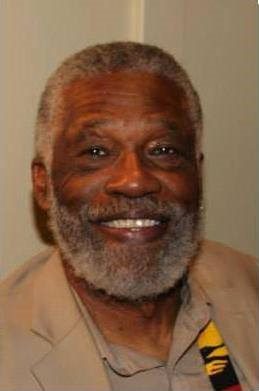

EDITOR’S NOTE: Former Tucson High School and University of Arizona basketball standout Ernie McCray is a legendary figure to Tucsonans and Wildcat fans. McCray, who holds the Wildcats’ scoring record with 46 points on Feb. 6, 1960, against Cal State-Los Angeles, is the first African-American basketball player to graduate from Arizona. The university reportedly will honor McCray by adding him to its Ring of Honor. McCray, who now resides in San Diego, earned degrees in physical education and elementary education at Arizona. He is a longtime educator, actor and activist in community affairs in the San Diego-area. He wrote a column for now-defunct TucsonCitizen.com and has agreed to continue to offer his opinion and insight with AllSportsTucson.com. McCray also writes columns for SanDiegoFreePress.org.

Someone on Facebook posted “What’s the best Christmas gift of your life?”

My answer was swift: a bike.

I’ll always remember the Christmas it became mine. It was in 1947 when I was nine.

That morning, though, I was down as down could be. Because my mother had led me to believe (and she had never ever deceived me) that this Christmas there would be a bicycle under the Christmas Tree for me. But when I woke up that was not the reality.

I was crushed, to say the least, and I couldn’t hold my feelings inside and if my family had been an ass whuppin’ kind, my mother had a reason to tan my behind…

And after a little time of me giving my mother and the world a piece of my mind she says to me, giving me “the look” mothers flash when they’ve had enough of your ungrateful ass: “Shut your mouth and put your new jacket on. We’re going to Sergeant Hudson’s house to wish him a Merry Christmas.”

I quieted myself but I was still beside myself, wondering why we’re going to this man’s house. Now, I liked the good sergeant. He was a dear family friend. And he was fun, a natural born comedian who could make people bend over with laughter listening to his wild stories about World War One, a war that somehow spared him the pain I saw on other old soldiers’ faces when I was growing up. Maybe he was laughing to keep from crying.

Any way you look at it, though, he was a wonderful man. He let me pick peaches off his tree and ride on the sideboard of his car and he paid me handsomely when I helped him with his chores.

But none of that matters when your heart is broken, when your faith in humanity has crashed, when your mother, in your mind, has strung you along. For what, you don’t know.

I wanted to die when Sergeant Hudson greeted us on his front porch, a vision of holiday spirit, wearing the pointed hat of his military days, saying “Let me get that door for you, son” – and when it opened I was suddenly a boy overwhelmed “with tidings of comfort and joy” as right in front of me and in front of a Christmas Tree was a blue Schwinn with white trim.

My mother stood watching me, as I danced to the tune of my happiness, with tears on her face, having just re-won my faith in her. We hugged each other’s cares away and “before,” as they used to say, “you could say Jack Robinson” I was out the door pumping away.

I’ve never been more happy and I don’t think I’ve ever doubted my mom since that day, having learned a little something about love and trust and friendship and such.

And I rode that bike from daylight to darkness, everywhere: up “A Mountain,” flying like the wind back down to town; out to the rodeo grounds and the greyhound racing grounds; out to Randolph Park where the Cleveland Indians trained; on the campus of the U of A.

It was so freeing, as I could give way to questions that came to my mind as I biked here and there, comparing where I lived in a Black part of town, near a Mexican American Barrio, with neighborhoods I was now getting a good look at, neighborhoods where I could not reside, so many of them with beautiful colorful gardens and two car garages and spacious driveways.

And I wondered what it was about me that they wouldn’t want me to live next to them when I was smart and nice and well-mannered (minus moments like having a mental breakdown on Jesus’s birthday).

Similar thoughts rose up as I wheeled by swimming pools where I wasn’t allowed to swim and schools that I couldn’t attend.

It was confusing to me that people like me were seen as “not so smart” when I had, that year, with other of my peers, represented Dunbar, the all-Black school, in a win against White schools on a radio quiz show.

How could we be considered “less than” when our school had the best teams, the best chorus, the best majorettes and the best marching band?

But life unfolds in stages, and my bicycling in my boyhood, like my world travels as a man, let me gradually come to realize that there all kinds of sides to people, that we, no matter where we exist in the universe, are more alike than different, that there’s a lot of love in play in the world even when it doesn’t seem so.

Such thinking, thankfully, has enabled me to open myself to different surroundings and experiences as a pathway to having a pretty nice life.

I owe so much of that to a bike.

The best Christmas gift of my life.