FOLLOW @JAVIERJMORALES ON TWITTER!

[rps-paypal]

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

— General history

— J.F. “Pop” McKale

— The games

— Comparisons then and now

— Wildcats nickname

— Military service

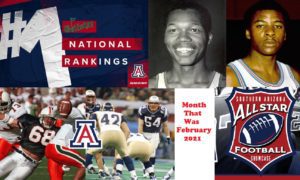

— Rankings

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Excerpt from L.A. Times, Nov. 8, 1914, authored by Bill Henry:

“Arizona’s cactus-fed athletes, despite heroic efforts on the part of their two halfbacks, (Asa) Porter and (Franklin) Luis, went down to defeat before the Occidental Tigers yesterday afternoon, the tally with all precincts heard from being 14 to 0 in favor of the Tigers.

Confident of rolling up a big score, the Tigers took the field with grins on their faces, but before the game was 10 seconds old they knew they had a battle on their hands.

The Arizona men showed the fight of wild cats and displayed before the public gaze a couple of little shrimps in the backfield who defied all attempts of the Tigers to stop them.”This site will conduct a countdown in a 100-day period, leading up to Arizona’s 2014 football season-opener with UNLV on Aug. 29 at Arizona Stadium. The 100 Days ‘Til Kickoff countdown will include information daily about the historic 1914 Arizona team that helped create the school’s nickname of “Wildcats” because of how they played that fateful day against Occidental.

[/ezcol_1half_end]

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

Fred Batiste was Arizona’s first African-American football letterman in 1949

At the turn of the 20th century, when the historic 1914 Arizona football team played, Tucson was at the infancy stages of becoming a melting pot.

Many of the African-Americans who moved to Southern Arizona left the southern states looking for new opportunities to establish roots, raise families and escape racial persecution. Others came to the area as soldiers stationed at Ft. Apache or Ft. Huachuca or laborers with the Southern Pacific Railroad Company.

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

According to the Federal Bureau of the Census in 1910, only approximately 222 African-Americans lived in Tucson at that time. That number increased to only 346 by 1920. Tucson’s population in 1910 was only 13,193, a number that would not fill McKale Center today.

Although no records indicate that Arizona’s state universities were segregated, a minimal number of African-Americans attended the University of Arizona in the early years of the 20th century. Only 308 students were enrolled overall at the university in the 1914-15 school year.

High school education in Tucson at the time was segregated. Two years before the 1914 Arizona team played, when Arizona became a state, the Paul Lawrence Dunbar School for African-Americans opened in Tucson.

The 1914 Arizona football team that earned the honor of being named the first “Wildcats” was composed of (front row, left to right): Verne La Tourette, George Seeley, Leo Cloud, Richard Meyer, Asa Porter. Second row: Franklin Luis, Lawrence Jackson, Ray Miller, J.F. “Pop” McKale (coach), Turner Smith, Harry Hobson (manager), Orville McPherson, Albert Crawford, Ernest Renaud. Back row: Albert Condron, Emzy Lynch, Charley Beach, Vinton Hammels, Bill Hendry, George Clawson, Harry Turvey.

(AllSportsTucson.com graphic/Photo from University of Arizona Library Special Collections)

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

What they were talking about on this day in 1914

Thursday, June 25, 1914

Conflicting reports come from Paris as to the condition of Jack Johnson, who fights Frank Moran in the French capital June 27, to retain his heavyweight title. Fans are also in the dark as to the condition of Moran. A sign that times have changed: The Arizona Republican headline on this date — “Negro’s fast living may give the challenger title” — describing Jackson’s lifestyle.

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Tucson High School started to include students of all races in the 1920s, although homerooms were still segregated and there were restrictions on African-Americans to participate in many school activities. The secondary education system overall in Tucson had segregation until 1951.

After a stellar career at Tucson High, running back Fred Batiste became the first African-American to letter at Arizona in 1949. His exploits encouraged a wave of African-Americans to compete for the Wildcats.

Anthony Gimino, writing an article for the Arizona Republic last year, mentioned that Ernie McCray was inspired by Batiste. McCray, a blogger for this Web site, was another Tucson High grad who played basketball at Arizona from 1957-60. He holds the single-game UA record with 46 points against Cal State-Los Angeles in 1960.

“We lived in the same neighborhood,” McCray told Gimino of the Batiste family, including older brother Joe, a legendary Tucson track athlete.

“Fred was our hero, our first at the college level; up until it was the guys wearing the big red ‘T’ of Tucson High who made us sigh. Nice man. … And he could run, like Joe. If he got past the last man it was no contest. I don’t know what kind of student he was, but he sure opened some doors. As I remember, there was a lull as far as Black football players, and about the time I enrolled in 1956 that was changing.”

Hadie Redd was Arizona’s first African-American basketball player in 1951.

ALLSPORTSTUCSON.com publisher, writer and editor Javier Morales is a former Arizona Press Club award winner. He also writes articles for Bleacher Report and Lindy’s College Sports.