Ernie McCray

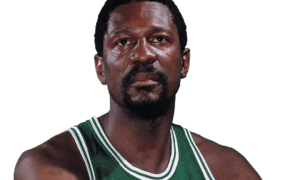

EDITOR’S NOTE: Former Tucson High School and University of Arizona basketball standout Ernie McCray is a legendary figure to Tucsonans and Wildcat fans. McCray, who holds the Wildcats’ scoring record with 46 points on Feb. 6, 1960, against Cal State-Los Angeles, is the first African-American basketball player to graduate from Arizona. McCray, who now resides in San Diego, earned degrees in physical education and elementary education at Arizona. He is a longtime educator, actor and activist in community affairs in the San Diego-area. He wrote a blog for TucsonCitizen.com before the site ceased current-events operations last year. He agreed to continue offering his opinion and insight with AllSportsTucson.com. McCray also writes blogs for SanDiegoFreePress.org.

[rps-paypal]

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

When I look back at my own little chapter of Black History, I feel grateful that I found a path that enabled me to survive a society that sought to deny me a life of dignity.

I, unknowingly, set out on this path on my first day of school, when my knuckles were, seemingly, knocked to kingdom come because I had dozed off, as if I had a choice in a room sizzling at 100 and some degrees with a fan (itself struggling to stay awake) blowing across a pail of water as though that could lower the temperature in that room to any degree. I swear I heard that fan wheeze. Talking, Tucson, Arizona, August or September of 1943.

I remember thinking, back then, as I looked at my hands, surprised to see my knuckles still there, “What the hell kind of welcome was that?” And I knew, as much as a five-year old can know such things, that someday I would be a teacher.

I would observe goings on in every school I ever attended, thinking of what I might have done differently if I had been the teacher. I’d imagine how I would have made lessons come alive, or more relevant to students’ lives.

Also along the way, I had to learn to navigate a world that loudly told me, then constantly reminded me of: what I could or couldn’t do; where I could and couldn’t eat; where I could and couldn’t swim; where I could and couldn’t sit at the movies or on the buses; what water fountains I could and couldn’t drink from.

It was a mess, sometimes macabre even, like down South if I were to look a white woman in the eye, I could be left dangling from a tree – to die.

And in the summer of ’49, in Detroit, when I was eleven years old, Jim Crow really put on a show for my young self to see, leaving me standing, shaking in horror, as fire fighters soaked a fire the KKK had started on my cousin’s house (with my mother and him and me in it) because he had dared to move into a white neighborhood.

I had a lot to talk about when that summer ended and I showed up for my sixth grade year at Dunbar Elementary/Junior High, an all-black school, two years before a brave white school superintendent said enough to such nonsense.

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Ernie McCray during his Arizona playing days. His 46 points in a 1960 game remains a school record (University of Arizona photo)

[/ezcol_1half_end]

(Flickr creative commons photo)

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

Dunbar then became John Spring Junior High, named after an Arizona pioneer. Changing an iconic school’s name was a lesson in politics that opened my eyes more to the ways of the world.

But I stayed on my path, becoming the president of my 9th grade class, giving a graduation speech steeped in my growing philosophy that “if you reach for the stars you might reach the moon.”

I was definitely feeling my oats, eyes so focused on the prize, having already, years earlier, decided not to take what life was dishing out sitting down.

Like one day when I was maybe 9, I had to take a deep breath to get up the nerve to tell the director of the YMCA, who was an okay guy, on the whole, that I didn’t like it when he called me “Eight Ball.” He stopped. I don’t know what I would have done if he hadn’t but I don’t think that’s the point. You have to speak up against injustices.

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Getting involved in matters was passed down to me, as I grew up around politics, knocking on doors with my mother for candidates we thought to be in our corner, helping out at “get out the vote” barbecues in my neighborhood, challenging Tucson’s Jim Crow Laws with a group called SFE, Students for Equality, at the U of A. I’m a Wildcat to this very day.

The path I took was rich with valuable lessons about life in the U.S.A. And it all, every life experience I ever had, came in handy when, in August of 1962, as a 24 year old, I showed up as the new sixth grade teacher at a school in San Diego, a school located in a naval housing complex.

When I arrived, many of the fathers of my students, were engaged in the Vietnam War and because I understood the fears that children have during war, as World War II and the Korean War were significant in my life, we talked about what was going on and how they were feeling. We wrote prose and poetry and made reel to reel tapes to send overseas to the men they were missing desperately.

South Africa came to our attention and knowing a little something about racism I was able to help them understand what was going on.

There was very little “sitting quietly” in our room of learning, little to no being told what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. I wanted to arouse their curiosity and creativity. I wanted to leave them with ideas that might lead them to creating a world far more loving and respectful of all people than the world that greeted me on April 18th, 1938, at St. Mary’s Hospital in the Old Pueblo.

So we dissected the tragedies of our times, the demise of the likes of Medgar Evers and JFK and Malcolm and MLK and RFK and talked of ways a better world could be created, that it couldn’t happen if we, as citizens, joined in with our society’s silent majority, all weighted down with apathy and a lack of empathy and sympathy.

Getting involved in matters was passed down to me, as I grew up around politics, knocking on doors with my mother for candidates we thought to be in our corner, helping out at “get out the vote” barbecues in my neighborhood, challenging Tucson’s Jim Crow Laws with a group called SFE, Students for Equality, at the U of A. I’m a Wildcat to this very day.

Out of respect for them I had to walk my talk so I was out and about trying to “Free Huey” and end the war. I joined the energy of black leaders who were spreading their wings in our struggles for justice and opportunities in my adopted city.

Then, overtime, on the path that I was on, I ended up as a principal of several schools, known for my outspoken-ness, which was unavoidable considering some of the ridiculous things a school district can do.

Like using undercover cops to deal with drug problems on our campuses, something which I thought was downright deceitful, a betrayal of the young people whom we were charged with nurturing into learned and caring human beings. It’s hard to educate folks who are distrustful of you.

One year I had to speak out against the district not taking a stand against teacher’s retirement funds being invested in companies doing business in South Africa, pointing out the audacity of being in the process of “integrating” our schools while, at the same time, supporting Apartheid.

Then there I was in 1994, with four other principals, refusing to honor Proposition 187 that required us to screen families to see who might be “illegal aliens.” With the discrimination I had encountered in my life, and with the path I was on I was left with no choice other than say “Hell No!” to such an initiative.

Incorporating my life and beliefs in the learning communities in which I’ve been involved is what healed me, is what kept me from being an angry broken black man with nothing to give.

Along my path I found that the more I shared who I was and what I stood for, the more students leaned forward to hear what I had to say, the more they understood the world and how they might fit into it and the better chance they had of finding a path of their own.

My path has brought me more love than I could have ever imagined. And I remain on that path as it has not come to an end. My little chapter of Black History has taught me that creating a better world for all people is a path that never ends.

I welcome anyone anywhere to step onto that path with me.