Ernie McCray

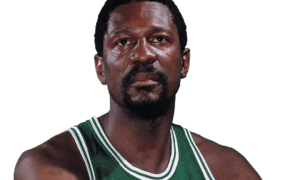

EDITOR’S NOTE: Former Tucson High School and University of Arizona basketball standout Ernie McCray is a legendary figure to Tucsonans and Wildcat fans. McCray, who holds the Wildcats’ scoring record with 46 points on Feb. 6, 1960, against Cal State-Los Angeles, is the first African-American basketball player to graduate from Arizona. McCray, who now resides in San Diego, earned degrees in physical education and elementary education at Arizona. He is a longtime educator, actor and activist in community affairs in the San Diego-area. He wrote a blog for TucsonCitizen.com before the site ceased current-events operations last year. He agreed to continue offering his opinion and insight with AllSportsTucson.com. McCray also writes blogs for SanDiegoFreePress.org.

[rps-paypal]

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

There’s a school that means the world to me: Oliver Hazard Perry Elementary. It’s the first school to which I was assigned after earning a teaching degree.

It was a place of colorful personalities: a teacher who sang opera beautifully and wore a hairpiece that could be identified as a wig immediately; a school nurse with a drawl as southern as any character’s on Hee Haw; a lovely and entertaining secretary who made the school office as funny and lively as The Carol Burnett Show…

It was a place of uncommon camaraderie where we: put potlucks together practically every other week; dined together monthly at fine places to eat; played volleyball after school; partied wildly at the drop of a hat, with lampshades on the head and stuff like that…

Now, it wasn’t all that bright and sunny looking to me when I first stepped into that building in August of 1962, all pumped up and set to do what I was hired to do.

I mean when the principal shut the door and walked away from the classroom he had just led me to, I was left standing there, shaking in my size 14 shoes, surrounded by: bare light green walls and equally bare white bulletin boards and uninviting looking desks and chairs scattered here in there. I’ve never before or since felt quite so uncertain and all alone.

A week later the walls were still just that, and the bulletin boards were filled with whatever my concept of “attractive and vibrant” happened to be and sitting in the chairs at the desks I had carefully arranged (based on the vice-principal’s theories on children and learning as it relates to how and where they’re seated) were about forty 6th graders the summer hadn’t worn out in the least.

After a couple of weeks I was ready to head to the cotton fields or work in a dynamite plant or recycle dead animals, anything that didn’t involve being eaten alive by 11 and 12 year olds.

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Ernie McCray during his Arizona playing days. His 46 points in a 1960 game remains a school record (University of Arizona photo)

[/ezcol_1half_end]

The first school Arizona basketball legend Ernie McCray taught at in San Diego, Oliver Hazard Perry Elementary School (Ernie McCray/AllSportsTucson.com)

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

Oh, I was doing okay when I think about it. Pretty good in fact. But I wasn’t myself. I was out of rhythm. Out of rhyme. Kind of dying before my time.

Then Thanksgiving came and I drove me and my family home. And as I laid my eyes on my mother and my friends and so many familiar streets and pathways and the mountains that circled the town and ate some barbecue at Jack’s and danced to some music at the VFW – I came alive. At the same time I realized what had been ailing me. I had been homesick. Terribly.

And no wonder. No one should leave a town where they’ve spent the first twenty-four years of their life in the way I had gone about it. I mean, come on. On a Friday, I took an exam for my M.Ed and worked a shift on the job I was quitting. On Saturday I spent part of a day and night driving from Tucson to San Diego. Sunday I spent stretching my legs. Monday I’m in a bungalow, in a town called the other city by the bay, wondering “Where the hell am I?”

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

But when I returned to that classroom I felt all charged up like I use to feel when we played the Arizona State Sun Devils or I was matched up against any school’s hotshot star. My students and I started really getting to know each other and having a good time. The school year ended with a bunch of kids having become good friends of mine.

At the Sixth Grade Promotion Ceremony I was in for the surprise of my life. I mean I was caught way off guard. It came when the principal introduced each of the sixth grade teachers to the audience of parents and families and their friends:

“In Room B3, Mrs. Jones.” That filled the auditorium with polite, yet peppy, applause. Rightfully so, because Mrs. Jones knew her craft and practiced it well. “In Room B4, Mr. Smith.” Same thing. He was masterful too. “Room B5, Mr. McCray.”

Before I could stand all the way up and do my little bow, the auditorium erupted into folks jumping to their feet, clapping and filling the room with “Yay!”

Man, how validating could anything be. All I have ever wanted to do in a classroom is touch the hearts and souls of learners as well as their minds. And my school community that year, and the next five years that followed, with the assassinations and the great social movements in the streets and the War in Vietnam and all, didn’t mind that I had students:

– Putting pen to paper to vent their feelings so they could heal after these tragedies and look at similar situations in the past, seeking truths among so many lies;

– Getting to know leaders like Martin and Malcolm by truly listening to what was and wasn’t being said about by them (beyond what we were reading in the news or seeing on TV) and then staging scenes, through improvising and script writing;

– Gleaning deeper meaning out of what was before them by singing and dancing to the beat of those troubled times.

It was particularly important, it seemed to me, that at a school like ours in naval housing, with so many of my students’ fathers off to war, that they write poetry and make reel to reel tapes of them reading their poetry to send to their dads.

Oh, those days were both heady and shocking, but with so many parents in tune with what I had to give starting from the time I arrived, and with the Esprit de Corps I earlier described, my days at Oliver Hazard Perry were simply divine.

I’m so glad I was there at such a critical time in human history, learning how to help students make sense of their world by looking at it critically.

My first teaching job got me off to a running start as an educator. For that I am forever grateful. When it comes to my days there I can’t help but have sweet memories and I’d do it again in a heartbeat if such a reality could ever be.