Ernie McCray: “

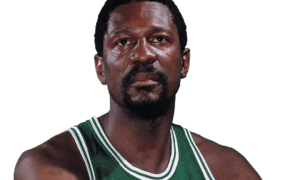

EDITOR’S NOTE: Former Tucson High School and University of Arizona basketball standout Ernie McCray is a legendary figure to Tucsonans and Wildcat fans. McCray, who holds the Wildcats’ scoring record with 46 points on Feb. 6, 1960, against Cal State-Los Angeles, is the first African-American basketball player to graduate from Arizona. McCray, who now resides in San Diego, earned degrees in physical education and elementary education at Arizona. He is a longtime educator, actor and activist in community affairs in the San Diego-area. He wrote a blog for now-defunct TucsonCitizen.com and has continued to offer his opinion and insight with AllSportsTucson.com. McCray also writes blogs for SanDiegoFreePress.org.

[rps-paypal]

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

I’ve been thinking about my man, Muhammad Ali, off and on, feeling sad that he’s gone. But as a contemporary of mine (he was four years younger than me), he’ll never be forgotten by me because he has meant the world to me.

When I first heard about him he had just fought his way to a gold medal as the light heavyweight boxing champion in 1960 at the Olympic Games in Rome.

I had just graduated from Arizona with a degree in P.E. and all kinds of basketball scoring records. So he and I were two young black men, athletes, standing tall and all. Who knew, though, that he would take being a sports figure to levels that were, up to then, unseen.

He was Cassius Clay in those days, but not a household name yet, although, every now and then, on sport pages there would be tidbits about this brash mouthy boxer who was fleet of foot and hand; the toast of the Olympic Village where he went around shaking hands and making friends, with a beautiful smile on his face.

I had no idea, of course, at the time, that this man would become someone who I would come to deeply love and respect; someone huge in the company of my heroes.

But it wasn’t love at first sight. Like many people I didn’t realize what was happening when Cassius got his show on the road. I mean I like rhyming and playing with words but citing poetry about the ass whuppin’ you’re about to put on somebody, or the one you just put on somebody, didn’t seem very sportsman-like to me. I was only in my early 20’s but I was old school about stuff like that.

One of the reasons I didn’t care about him was because he cost me some dough, only a buck or two, but dough never-the-less for a beginning teacher with a wife and three kids, all of whom liked to eat.

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Ernie McCray during his Arizona playing days. His 46 points in a 1960 game remains a school record (University of Arizona photo)

[/ezcol_1half_end]

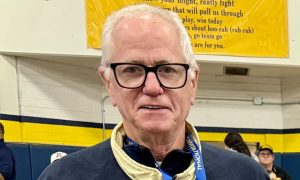

Ernie McCray writes about Muhammad Ali: “He spoke for justice, peace, freedom, and equality for all races.” (Flickr.com photo)

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

Like I remember sitting in my living room, in Februrary of 1964, waiting for the Clay-Liston fight, knowing I’m going to have me about five more dollars in my pocket after the fight than I had at the beginning of the fight — because Sonny Liston was a monster, Jack! A beast! A killer of men! But the bell rings and Clay was on Sonny like stink on a sulphur pit. Dude decided to sit out the seventh round. And I had trash talking friends snatching bills out of my hand in the manner of highway robbers.

Oh, but Sonny’s going to get him next time (May, 1965) I remember thinking. I saw the first fight as a fluke but before I could pop the top off a beer, in the rematch, Cassius Clay, now Muhammad Ali, good friend of Malcolm X, looked at a feeble left lead of Liston’s that I could see coming from my couch and unleashed a right that went upside the man’s head with the swiftness of a cobra strike. It was a lightning fast punch even in slow motion.

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

I tried to get behind Ali at this point, thinking that if Malcom likes him who am I not to like him, and he was already speaking out against injustices in our country as I was doing. But he was due to fight my boy, Floyd Patterson. You had to love Floyd for his prowess as well as his bravery because anybody with a glass chin should stay out of the ring.

I was bothered that Floyd refused to call Ali by his new name but, at the same time, I didn’t like that Ali was calling him an “Uncle Tom” and “The Rabbit” because “he’s scared like a rabbit.”

Ali toyed with Floyd in their bout instead of just knocking him out but the way he defended his actions spoke to me powerfully: “Yes, I carried him for six rounds” he said to those who had criticized his “disrespectful” behavior in the ring against a beloved pugilist. “I am showing you good boxing. You’d be the first to condemn me if I killed him cruelly.” I sensed in that something truly human, something beyond the kind of carnival atmosphere this superb prizefighter had generated around himself.

Then, in 1967, in my late 20’s, when I was still trying to define who I was as a black man and an American, moved by what was happening in the country in the area of civil and human rights – Muhammad Ali did something that endeared himself to me forever.

He said, in essence: “Hell, No, I won’t go!” to the U.S. military.

That really caught my attention. I knew, at that point, that Ali truly was the real deal, that he was fully committed to his people. He very likely, if he had served, would have been used in some special way, boxing in exhibitions as a poster boy for the military, so he could entice young men to take heed to “Uncle Sam Wants You.”

Instead he, in accordance with his strong determined opposition to how black people were treated in America declared: “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?”

The beauty of this to me was the whole world heard what he had to say. He spoke for a race. And he spoke for justice, peace, freedom, and equality for all races.

If there is such a thing as a godsend, this beautiful man who “floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee” was it. RIP, my brother.

You were, indeed, “The Greatest!”