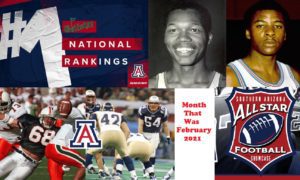

Ernie McCray

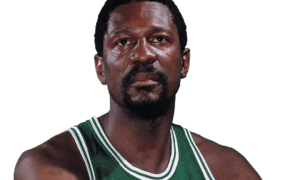

EDITOR’S NOTE: Former Tucson High School and University of Arizona basketball standout Ernie McCray is a legendary figure to Tucsonans and Wildcat fans. McCray, who holds the Wildcats’ scoring record with 46 points on Feb. 6, 1960, against Cal State-Los Angeles, is the first African-American basketball player to graduate from Arizona. McCray, who now resides in San Diego, earned degrees in physical education and elementary education at Arizona. He is a longtime educator, actor and activist in community affairs in the San Diego-area. He wrote a blog for TucsonCitizen.com before the site ceased current-events operations recently. He agreed to continue offering his opinion and insight with AllSportsTucson.com about Arizona Wildcats athletics. McCray also writes blogs for SanDiegoFreePress.org.

BY ERNIE McCRAY

Special to AllSportsTucson.com

With Father’s Day today, I’m thinking back to how I used to kind of dream of being a dad when I was a little boy.

The concept of fatherhood has held some significance to me for most of my life. One of my first questions to the universe was “What does a daddy do?”

That was all about the fact that my mother was the one in my everyday life, working, as she would not let anybody forget, her fingers to the bone. And that was confusing to me since my dad, who didn’t live in our home, seemed to be resting and dressing and cruising – and I felt forced to get a job when I was only five years old.

Now, this isn’t one of those tales of extreme poverty where the very survival of a family meant that the children had to go to work. Naw, my mother didn’t come up to me my kindergarten year and say that I had better get a job to keep us from starving to death. But I noticed that whenever I needed a little finance for one of my wants or business enterprises like the obligatory lemonade stand, my mother would start stuttering and coughing and reminiscing about the Great Depression (which didn’t seem so “great” to me the way she talked about it) and start in on how money didn’t grow on trees. Or she’d be trying to camouflage herself next to the icebox (not refrigerator) to avoid discussing my money desires with me. She just didn’t have the finances at the ready and my social obligations were already pretty heady.

Ernie McCray with his six children (McCray family photo)

I mean I couldn’t pass a store without wanting to empty it of all its ice cream cones and popsicles and peanuts and crackerjacks and tons of other snacks. And I was bent on keeping up with all the stories in all the comic books and keeping myself supplied with caps for my toy pistols and jacks and odds and ends like electric train tracks. I needed marbles by the pound and strings for yo-yos and balloons to blow up or attach to the water hose. There was absolutely nothing that was free so I had to get me a j-o-b. All the while I just couldn’t figure out why my papa didn’t bust his butt to help my mother and me.

So becoming the “man of the house” really appealed to me and I felt pretty important when I became an employee. My first boss was a shoeshine man, a family friend named Osie.

I sure enough thought I was hot stuff but I can still hear Osie’s voice: “No! No! No, son! Shine the man’s shoes, not his socks.” And that was easier for him to say than me to do because he was a pro, but I was trying to be a pro too. But with my lack of age and dexterity I had to bid that dream adieu. Osie was the man. The man. He could flat out shine some shoes. He’d be poppin’ his shoeshine rag on people’s stomps like he was Mongo Santamaria or somebody: “Slappity pap pap slappity pap pap slappity pap pap pap.” Osie was the haps.

It was infectious. People would pass by and say: “Go, head on, Osie, you all reet!” and they would whistle or move a while to the beat. Some of them would be tired on their feet from a day’s work but, goodness knows, the rhythm would get them up on the toes of their feet. Ninety-year old grandmothers would sashay by like Ginger Rogers or Shirley Temple on a movie set street.

I would often think, back then, in whatever way a five-year-old can think such thoughts, about how when I became a daddy someday I would shine so many shoes so well that I would be rich and no wife of mine would have to sell Avon and do taxes and cut hair and clean up the telephone company’s floors Monday through Friday and Miss Sally’s fine house on Saturday. No way. We would be rich and live happily forever and ever.

That’s the dad I wanted to be. One who would do anything to make life go as well as can be for his family. I think that’s the dad I’ve been but I know I’ve enjoyed the journey.

[rps-paypal]

|

|