Julius Holt, a substantial member of the Tucson community since his playing days with the Arizona football program in the early 1980s, has passed away at age 60.

Holt died early Monday morning with his family by his side — wife Lisa, son Justin and daughter Julia.

He was stricken with pneumonia and passed away after being hospitalized since early last week. Suffering from heart problems in the past, and wearing a pacemaker, Holt was placed on a ventilator in an intensive-care unit.

Many in the Southern Arizona community offered their well-wishes and prayers on social media upon learning the news of his health status.

Julius was excited about the prospect of Julia, a senior at Canyon del Oro High School, signing with Howard University on a softball scholarship and being able to play where he was born — Washington, D.C. He talked about looking forward to watching her play there with some of his family who are in D.C.

“I am proud of her and very happy she is going to a university like Howard,” Julius told me. “It’s a great opportunity for her and our family.”

His son Justin was a standout lineman at Salpointe Catholic who played in 2016 and 2017 at Arizona, wearing the No. 50 Julius wore with the Wildcats, before he was forced to medically retire from football because of concussion problems.

Julius became the president of the Tucson Youth Football and Spirit Federation in 2013, an organization he viewed as being much like the Boys and Girls Club back in D.C. during his childhood. Julius also worked as a high school counselor and program coordinator for middle school sports at Tucson Unified School District.

He was inducted in the American Youth Football Hall of Fame in 2020.

After resigning as the TYFSF president, he mentioned one of his objectives was to become a motivational speaker for youths in Southern Arizona.

Holt’s life before coming to Arizona to play for Larry Smith in 1981 could have derailed many times, starting when he was growing up in the projects of Washington, D.C. His parents died within a month of each other while he was in the fifth grade. His parents Bernard Holt and Mary Holt remained neighbors after they divorced. Bernard lived at 1103 R Street, and Julius and many of his nine brothers and one sister stayed with his mom at 1105 R Street.

“When my mom had a problem, she would just knock on the wall and my dad would come over,” Julius said in a 2020 interview.

Bernard served in World War II and played baseball in the Negro League. Upholding the family name with class left a mark on Julius.

“My dad was one of the sharpest dressed people I ever met in my life,” Julius said. “I never saw him dirty, never seen him unkempt. He was clean. Slacks, nice shirt, tie and a little Fedora hat. Stuff like that. That was him every day.”

Mary worked long hours as a cook at the People’s Drug Store in downtown D.C., when stores like that had cafes in the back. Her work ethic motivates Julius to this day and her discipline was valuable for him to mature when she was gone.

“She wasn’t afraid to take that slipper off, to grab a belt or whatever she had to do,” he said. “She made sure you weren’t ripping and running and doing something stupid. When you did something stupid, you had consequences coming to you.”

With such influential personalities no longer with Julius, he could have become a victim of the streets in D.C.

His stepfather Willie Terry was a Godsend. He remained with Julius and the other kids. He navigated Julius during that difficult time and remained a mentor until passing away almost 20 years ago.

Willie also served in World War II and worked in construction. When inclement weather prevented him from working, “he was hustling and trying to make ends meet,” Julius said. “He was a little man who made big sacrifices dropping out of school in the seventh grade to work.

“My real dad was educated but my mom didn’t finish high school. We were dirtball poor. My stepdad used to load us up in his old green pickup truck and took us to motorcycle races in Virginia. That was our entertainment. To do that was a treat. Just going to McDonald’s when I was a kid was a big event. It really was.”

Julius’ older brother Bernard Jr. and his stepdad made him become involved with the Boys & Girls Club, and that’s where Julius’ love for sports and team bonding generated.

“My brother Bernard was the most important athlete in the world who I looked up to, the best role model I ever had,” Julius said. “He always made sure that I was doing something, that I was somewhere and not on the streets.

“Having the Boys & Girls Club there, that raised me up. We were allowed to play football, basketball and baseball. We had ping-pong tournaments. We had Easter three-on-three basketball tournaments right there in the back of the boys and girls club. That was big for me.”

The next obstacle Julius had to clear to keep his life on track happened when he was playing football at Cardoza High School in D.C.

At that time, Julius, nicknamed “Big Red” growing up because of his height and light complexion, said he was “five minutes away” from being arrested with another brother, who spent 17 years in prison. Julius said he was to meet his brother at a skating rink but was five minutes late because — being the proper person he was just like his dad — he ironed his clothes, including his jeans and trench coat, before heading out.

“By the time I get up there, it was shut down … nothing but police and the whole nine,” Holt said. “My brother did some things that he shouldn’t have done and I know if I had been there with him, I would have probably been doing those 17 years.

“I always ask myself, ‘Why was I five minutes late? Why did somebody choose me to be five minutes late?’ I’m thankful for those five minutes.”

Holt said he was grateful for Cardoza coach John T. Nun and assistant Frank O’Leary “coming to my aid and saving my life.” O’Leary made sure Julius went to school every day by picking him up at 7 a.m.

“They saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself,” Julius said. “I played football so I wouldn’t go to jail and that’s the truth.”

College football coaches started to pursue him when he was a senior linebacker at Cardoza. With his grades a concern, he signed a letter of intent with a smaller school, North Carolina Central, although schools such as Syracuse, Pitt and Boston College were interested.

Before Julius could make it to Durham, N.C.. to attend North Carolina Central, the head coach there, Ray Greene, was lured away by Alabama A&M to coach.

“The only reason why I was going there was because of him,” Julius said. “I had to go through the whole thing of getting released from my letter of intent.

“When I got around to trying to go somewhere else, Virginia Tech and Maryland were also interested. It was tough because of my grades. I had a 1.99 GPA. I wanted to go to Syracuse but because of my grades I couldn’t. It was nobody’s fault. That was just me not knowing what I wanted to do. I just wanted to do enough right to graduate from high school.”

Imagine if Greene did not leave North Carolina Central or Julius had qualifying grades to go to Syracuse. He probably would have never stepped foot in Tucson.

Julius was lured away to Ellsworth Junior College in Iowa Falls, Iowa, of all places. The coach there Vern Thomsen had a pipeline of Washington, D.C., area players head that way to try to became major-college prospects. Julius joined six other D.C. area players at Iowa Falls. He was only one of only two who remained after the initial culture shock was too much.

He almost left, bus ticket in hand, but an assistant coach talked him into staying, promising additional playing time at linebacker, the position he loved.

Julius earned junior college All-American honors at Ellsworth his sophomore season in 1980. That’s when Arizona entered the picture as well as Michigan State, Minnesota, Louisville, Iowa and Nebraska. Tulane, coached by Smith at the time, started recruiting Julius when he was a freshman at Ellsworth.

When Smith became Arizona’s coach in 1980, he assigned offensive line coach Mike Barry to recruit him. Why was an offensive line coach recruiting a defensive lineman/linebacker?

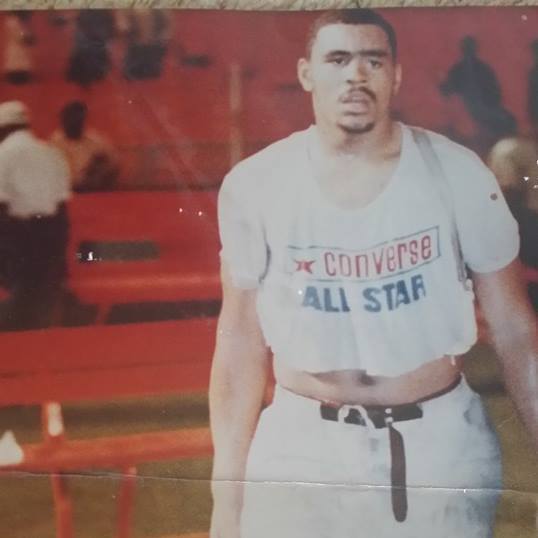

“Coach Smith sweared up and down that if I would have redshirted my first year (in 1981) and moved to guard on the offensive line, I would have played 10 years in the NFL,” said Julius, who was 6-3 and 263 pounds during his Arizona career..

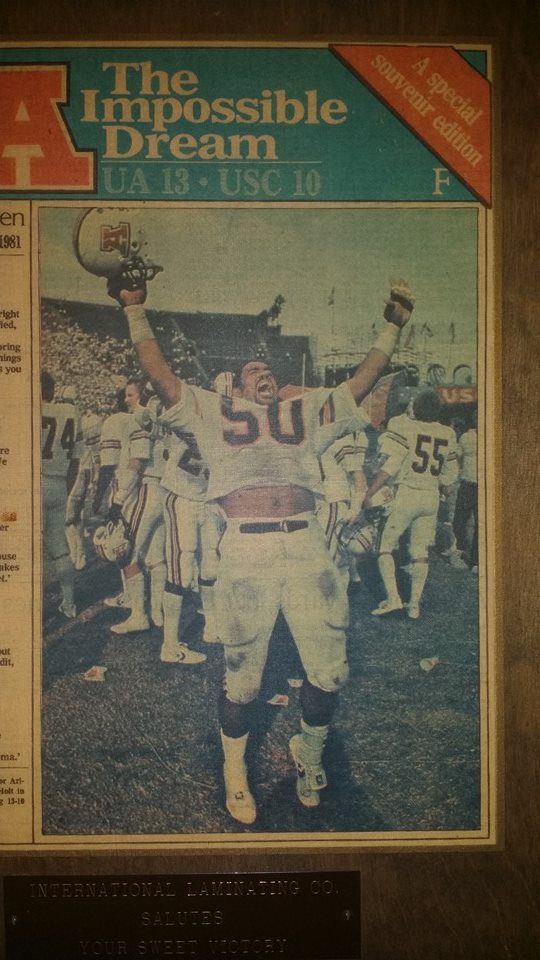

Julius, who purposely asked for a linebacker uniform number of 50, came to Arizona with the strong desire to play outside linebacker. Within the first two weeks of practice, Smith shifted him to defensive tackle and Julius tried to leave just like he attempted at Ellsworth.

“I packed all of my stuff and headed to the airport with a plane ticket bound to Minnesota; I was going to transfer there,” Julius said. “Coach Smith caught wind of it and got Mike Barry to go to the airport and talk me out of it.

“I stayed and not too long after that, my hand was in the ground as a defensive tackle. I was stuck because school already started. I just decided to stick with it and switch some of the time to linebacker.”

The university and Tucson grew on Julius.

He became the first in his family to earn a college degree in 1983 — a bachelors in Business and Public Administration.

He met his wife Lisa at Arizona.

The university kept him around to handle different responsibilities, including manning the room where coaches waited before going to the press-conference podium when the 1986 NCAA tournament first and second rounds were at McKale.

That’s about the time he started coaching in Tucson Youth Football.

In the 1990’s, he worked as an administrator and mentor in Arizona’s C.A.T.S. Program (Commitment to an Athlete’s Total Success). He became a positive influence for many athletes in different sports.

I just heard about what happened! I am heart broken! He was one of my academic advisors when I was a sa and we have remained friends over the years. Sending the Holt family prayers! 😭

— ADIA BARNES COPPA 🐻⬇️🌵👨👨👧👦❤️💙 (@AdiaBarnes) April 3, 2022

Imagine that, a young man at that time from inner-city D.C., struggling with his academics upon graduating from Cardoza, turning his life around enough to help others in an academic setting.

“I remembered some of the stars I saw play at Cardoza who never left our neighborhood and they were hustling to get by when I played there,” Julius said. “I looked up to them. They told me, ‘You better get up out of here. Get out of this rat race.’ That really got me thinking of making something of myself.”

“Julius has what I would call a service heart,” said Mirum Washington-White, TYFSF’s board consultant. “Because of his background and what he’s been exposed to — good, bad, ugly, indifferent, the whole nine yards — I think that allowed him to come at things from a service capacity.”

In an emotion-filled speech in October 2019 at the TYFSF awards banquet, Julius mentioned he was stepping down from his role as president because of his desire to watch Julia play softball during the fall at weekend tournaments and his health (he passed out and was hospitalized earlier that year).

The constant calls of operational clarification from team presidents and coaches and parents arguing about game situations took a toll on him. His wife requested that he relieve the stress by stepping down at that time.

All the while, Washington-White knew Julius was not going to depart because it would be “too tough on him to leave the kids and he always wants to make sure the operation is running smoothly.”

“I told him, ‘Don’t say you’re going to resign unless you’re going to do it,” Washington-White said. “We bet a steak dinner and so I was like, ‘You’re not walking away from this. You’re going to buy me the biggest steak because I knew what was going to happen. Sure enough, he did not walk away and he owes me a steak at Sullivan’s.”

Half of the league presidents told him to rip up his letter of resignation. The other half wanted to put it to a vote to keep Julius as the president. By a vote of 14-1, with the one person abstaining, he was elected to return as president. He agreed to stay and remained in that position through last fall.

He took the heat from many involved in youth football locally for cancelling the 2020 season amid COVID-19 concerns. A majority of the organizations were in favor of the cancellation for health safety concerns. The league resumed operations last fall with a full season.

He was grooming deputy commissioner Mike McCraren to take his spot as president before McCraren died in an automobile accident last October.

Don Riley was chosen the new president in February.

Julius’ stipend from being the president amounted to only $1,500 annually although he put in weeks of more than 40 hours. He was president only in title. He conducted himself like all the volunteers. He hawked TYFSF T-shirts at some games with the money going to the league’s operations.

“There are guys in other parts of the country who are presidents or commissioners of these leagues and they are getting paid $60,000 to $70,000 a year,” Julius said. “My loyalty and my responsibility is to these kids. All of my decisions will be based on what’s best for the kids.”

It was a long and incredulous path from near 11th Avenue and R Street in the middle of D.C. to living in northwest Tucson, supporting his family and carrying much of the responsibilities of TYFSF.

He could have become a victim of the streets after losing his parents before he was in middle school. He could have attended North Carolina Central or Syracuse instead of Arizona. He could have left either Ellsworth College or Arizona after becoming disgruntled.

Everything fell into place. It all worked out for Tucson and the city’s youths as well that Julius was around.

“My thing is I no longer live in D.C., so I can’t give a whole lot back there,” Julius said. “But I live here in Tucson, so what’s the best way of giving something back?

“Any chance you get, wherever you are, you should try to give back what you received when you were growing up.”

Funeral arrangements are pending. Julius is preceded in death by his parents Bernard and Mary, stepfather Willie Terry and brother Stephen. He is survived by his wife Lisa, son Justin and daughter Julia; many in his extended family; his Arizona football teammates and coaches; and countless friends and associates from the University of Arizona, Tucson Youth Football & Spirit Federation and the local media.

ALLSPORTSTUCSON.com publisher, writer and editor Javier Morales is a former Arizona Press Club award winner. He is a former Arizona Daily Star beat reporter for the Arizona basketball team, including when the Wildcats won the 1996-97 NCAA title. He has also written articles for CollegeAD.com, Bleacher Report, Lindy’s Sports, TucsonCitizen.com, The Arizona Republic, Sporting News and Baseball America, among many other publications. He has also authored the book “The Highest Form of Living”, which is available at Amazon. He became an educator five years ago and is presently a special education teacher at Gallego Fine Arts Intermediate in the Sunnyside Unified School District.